Dr Carla van Laar AThR

most of us have been socialised from a very early age to develop only two roles in our repertoire when it comes to art – “The Artist” or “The Critic”… The result can be that we internalise these two roles and our inner critic becomes so strong that our inner artist is stifled and shut down

“I can’t draw” – these are words most Arts Therapists are likely to hear many times in their working lives.

Often, our job begins with helping the people we work with to overcome obstacles that are deeply entrenched within themselves. These obstacles are internalised beliefs that “I can’t do it”, “I’m not good at art” or “It will look stupid”. The strength of these beliefs can be so powerful that they prevent people from even making a mark with a crayon from fear of “failing”. Taking even a tiny step towards creating something can take an enormous amount of courage.

Arts Therapists will recognise our familiar mantras, messages that we communicate to counter the dominant narrative that art is something only “good” artists can do. We say things like:

“There is no right way or wrong way to make art here”

“It’s about the process of making, not the end product”

We are trained to cultivate attitudes of non-judgement, and to assist others in developing this attitude too. This will often take a great deal of patience and persistence. Why? In trying to understand this, I find it helpful to consider that most of us have been socialised from a very early age to develop only two roles in our repertoire when it comes to art – “The Artist” or “The Critic”. When we make marks on paper as children we learn very quickly that others judge our efforts by telling us, or not telling us, that what we have made is good. Sometimes we are even told our creations are “no good”, or “wrong”. The result can be that we internalise these two roles and our inner critic becomes so strong that our inner artist is stifled and shut down.

we can contribute to the development of new and more empowering roles and ways of relating to art

Part of our job then, as Arts Therapists, is to expand the roles that are available to ourselves and others when it comes to our relationship with art.

In my book Seeing Her Stories, I presented the research findings from my ten years of Doctoral research into sharing our stories through art. One of the significant implications of my research for the practice of Arts Therapy relates to exactly how we can contribute to the development of new and more empowering roles and ways of relating to art. Part of this is what I call “facilitating multi-layered seeing”.

Here is an extract from chapter 10 of Seeing Her Stories that explains what I mean by “facilitating multi-layered seeing”, and how we can do it in our practice.

Facilitating multi-layered seeing

Facilitating multi-layered seeing

This research has illuminated the layers of experiencing that are possible to access through seeing artworks. The idea of multi-layered seeing challenges some culturally dominant seeing practices, and personal habits, which are often intertwined. Sometimes our seeing can be limited by common seeing practices that we are socially exposed to, and recruited into in our daily lives.

By simply noticing the visual images that we encounter in day to day life it becomes clear that those of us who live in, commute within and interact within developed and online environments will be subjected to copious advertising images. Noticing the effects that advertising images exert on us – such as feelings of desire, of jealousy, or of ugliness – is important, and conscious efforts can be made to reduce the influence of these commercial images. I advocate for clearing visual junk from our own spaces and blatant refusal to give advertising a home. I recommend that we surround ourselves with artworks that nurture our senses and provide an aesthetic rest from the demands and messages of advertising.

Art criticism emphasises the interpretation and evaluation of artworks, casting the viewer into the role of judge, and hence the artist becomes the judged

The discourses of art criticism have a major influence on how many of us experience having our own artworks seen in early life, for example in the art room in Primary School. Art criticism emphasises the interpretation and evaluation of artworks, casting the viewer into the role of judge, and hence the artist becomes the judged. If a viewer feels under-resourced to participate in this system, the result can be a sense of alienation from artwork and the institutions that exhibit them. As de Botton and Armstrong (2013) have highlighted, this is the dominant discourse that prevails in art institutions and galleries, and can result in viewers of art:

[leaving] highly respected museums and exhibitions feeling underwhelmed, or even bewildered and inadequate, wondering why the transformational experience we had anticipated did not occur. It is natural to blame oneself, to assume that the problem must come down to a failure of knowledge or capacity for feeling. (de Botton & Armstrong, 2013, p. 4)

In this discourse, there are only two roles available – the judge and the judged. It can be worthwhile to consider whether we identify more strongly with either of these roles, or have internalised these roles and habitually enact them, either with seeing our own artworks or the artworks made by others. Learning to identify and quiet the inner critic and/or the inner competitor is an important part of making space for cultivating ways of seeing that enable us to enact a greater range of roles as we engage in multi-layered seeing.

As Gilroy (2008) highlights, it is important for art therapists to be aware of how our seeing practices can be influenced by our own particular occupational contexts. For example, an art educator might be socialised to see through a cultural lens of evaluating conceptualisation and skill; a forensic clinician might learn to see through an institutional lens that magnifies risk of reoffending; a Jungian influenced psychotherapist might be inclined to see through a lens that is suited to focusing on symbolic meaning; a trauma informed therapist might see in a way that brings attachment styles to the foreground. Being aware of these influences can help us develop post-modern perspectives in which multiple ways of seeing are not necessarily in conflict with each other, but can co-exist within a multi-layered approach to seeing artworks.

Identifying and being mindful of cultural influences and dominant discourses in seeing artworks enables us to work at consciously disrupting their influence

Identifying and being mindful of cultural influences and dominant discourses in seeing artworks enables us to work at consciously disrupting their influence, and can assist us to cultivate alternative seeing practices. I use the themes of this inquiry as guides for accessing, cultivating and facilitating multi-layered seeing experiences.

Seeing can be practised as a bottom-up therapeutic activity that engages the senses, brings us into the here and now, and connects us with embodied experience. This can have therapeutic effects similar to those of mindfulness and meditation, as well as somatic experiencing. Some of these effects can include calming the mind, emotional regulation, engaging with pleasurable and supportive external and internal resources and listening to information that we gain through our senses and embodied experience.

This enriched understanding can be adapted for how we work in art therapy. One of the ways that I adapt my understanding of “seeing her stories” in practice is to use the artworks on the walls in my art therapy studio as part of the session. I sometimes invite a client, or even a whole group, to relax, breathe deeply, and look around the room until they find something that their eyes are drawn to that feels good or is interesting. I might ask questions such as “Out of all of these artworks, which are you drawn to? Notice your response, what draws your eyes to it, grabs you, leaps out at you? What seems important in the here and now?” As they engage in spending time to simply sit and be present with the artwork, I invite them to become aware of what is happening in their body, their breath, heart rate, emotions and in their mind, in their thoughts, memories and imagination. Allowing time for tuning in to their seeing as a whole body experience is important. This tuning in can provide an access point as viewers experience a resonance with their own values.

Through seeing, viewers can reflect on how they meet the artwork and what is important in that meeting. Seeing as a whole body experience can likewise be used as an access point to working with materials. In working with individuals or groups, I often create an engaging display of art materials and spend some time sitting with participants, inviting them to simply let their eyes rest on the materials, noticing what they are drawn to, and what they enjoy seeing. I encourage individuals or group members to notice any materials they would like to touch and play with using their hands, and to select the materials that give them sensory and visual pleasure. Paying attention to what is seen can inspire the urge in the viewer to make artwork in response to the seeing experience. The resulting artworks can invite a robust collaborative seeing together, a potentially potent process in which the art maker might experience really being seen through their own artwork as I, and perhaps others, also see their stories, and seeing artworks together becomes a way towards co-creative meaning making.

the art maker might experience really being seen through their own artwork

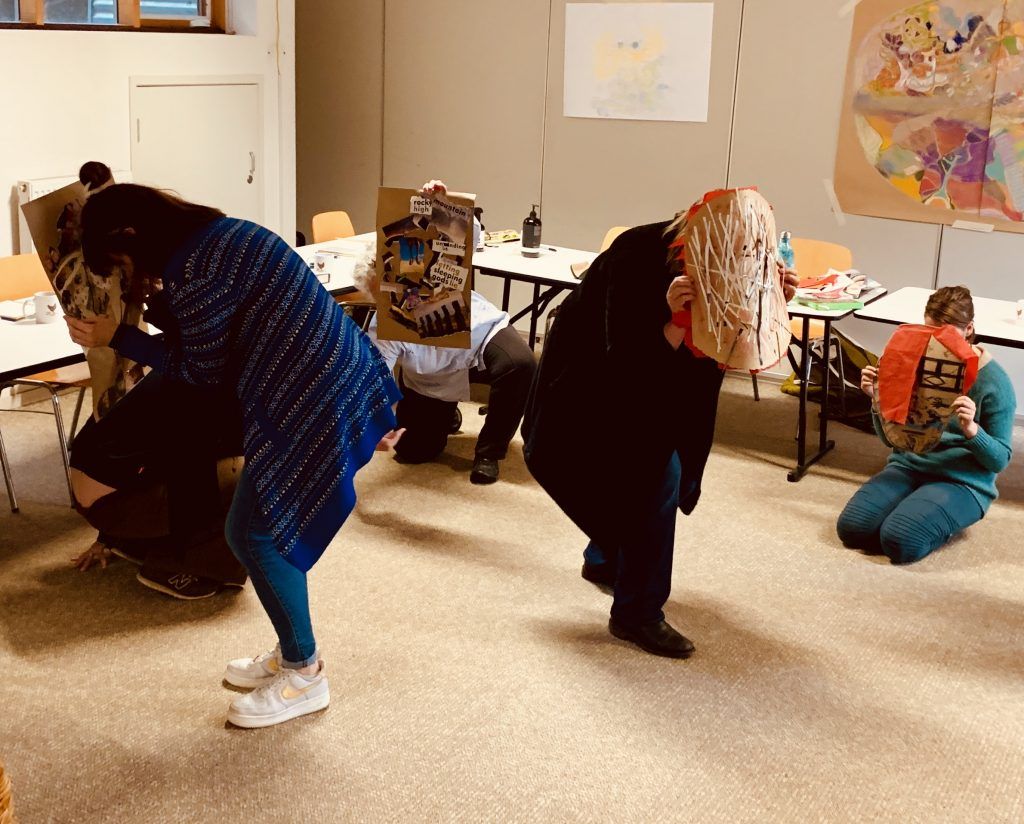

The understandings that have been produced through this project have implications for how we present educational opportunities for students. Here are some of the ways I have noticed myself using what I have learned in facilitating art therapy education with students.

I often use a “seeing art work” experience as the starting point for activities. This can bring a group into the here and now of their embodied experiencing, and can be very helpful when conversations become overly abstract or theoretical. I show slides of artwork, bring in books, take students on visits to galleries, or have them walk around the city looking for street art. I encourage them to find an artwork that reaches out to them, and practise sitting with it, being fully present, receiving the artwork through their eyes and their whole bodies rather than looking at it through lenses of dominant discourse or personal habits. I ask them to notice and journal about what happens for themselves in their embodied responses as they remain present with their seeing. These embodied responses might include movements of the eyeballs around the artwork, or the whole body through space including urges to move closer to or further away from the artwork, sensations that arise in the body such as tightness or tingling, emotions that arise and are felt as embodied responses such as to smile or produce tears, and responses that happen in the mind, including thoughts, memories and imaginings. This kind of exercise is a way of cultivating intentional presence with self and artwork, and can be expanded into developing skills in practising intentional presence with others.

When students are asked to collaborate on a group presentation, I have found it helpful to begin with seeing artworks together. This can help them to find shared interests as a way of group forming, and often leads to them feeling connected and engaged in the task at hand.

seeing and making artwork can be at once an individual sense activity, a mindful practice, a story, and a social action

Engaging in connection with our environment and contexts using our senses can be a starting place for art making. I sometimes facilitate this by inviting students to go outside and imagine that everything they see is a potential art material. This is possible in urban, built, or organic environments. Students are invited to create an ephemeral or guerrilla artwork using what is available and to leave it there as a response and contribution to our context. Reflecting on this experience highlights how context makes a difference in our experiencing, and the potentials for co-creating environments for ourselves and others. This can be a way of presenting the idea that seeing and making artwork can be at once an individual sense activity, a mindful practice, a story, and a social action.

Being aware of things that change and things that continue as they present themselves in our seeing experiences has implications for how we practise art therapy and work towards arts and health. For art therapists, we are frequently seeing the artwork made by the people we work with, although the idea of a fully in the present embodied seeing might not always occur. By practising our skills in present moment awareness and being mindful of our embodied responses to seeing the artworks of others, we can become attuned to changes in choice of materials, changes in process such as mark making, rhythm and pace, and changes in subject matter, composition or expression of emotions. We can notice and reflect these changes as a way of being present with the people we work with or our companions. Attending to change can provide hope that even in trying times, things are likely to change. As shown in the “Seeing her stories” inquiry, these can be things like perspectives, relationships, emotions and ways of being in life.

artwork can contribute to contexts in which diverse, embodied, authentic stories – and the people who make them – are welcome, acknowledged, valued and seen

In addition to noticing changes, we can be attuned to threads of continuity as we engage with other’s artworks. Noticing what continues, as we have seen in this inquiry, can connect us to a sense of relationship with our ancestors and culture, and with our continuing sense of self, by connecting us to things that are important to us, and our personal value system. Connecting with this sense of continuity of values within our lives can help us to remember, uncover, discover, generate and co-create stories that are meaningful, hopeful and empowering and make choices that support these continuing stories.

Attunement to continuity does not evoke conventional kinds of questions such as, “How can I change my behaviour / my emotions / my relationships / myself?”, but, rather, prompts reflective responses to questions like “How can I bring myself forward? How can I continue? What is important to me as I move from this present moment into the future?”. For groups or communities, these questions can strengthen a collaborative commitment to shared values and the enactment of preferred and empowering stories, as collectives of people consider together, “How can we bring ourselves forward? How can we continue? What is important to us as we move from this present moment into the future?”

Creative work can help us to see and understand patterns of experience that flow from our ancestors and cultures into our own ways of being. Seeing these patterns and engaging with them through the arts can enable new and restorative ways of responding, heal wounds that run back through generations, and create new, healthier, more productive ways of being that are passed on to those who come after us, our descendants. Artworks can be made that embody these stories, and the ongoing presence of the artwork can contribute to contexts in which diverse, embodied, authentic stories – and the people who make them – are welcome, acknowledged, valued and seen.

References

de Botton, A., & Armstrong, J. (2013). Art as therapy. London, England: Phaidon Press.

Gilroy, A. (2008). Taking a long look at art: Reflections on the production and consumption of art in art therapy and allied organisational settings. International Journal of Art and Design Education, 27(3), 251-263. doi:10.1111/j.1476-8070.2008.00584.x

van Laar, C. Seeing Her Stories. Carlavanlaar.com

Dr Carla van Laar

Artist | Art Therapist

Master of Creative Arts Therapy

Doctor of Therapeutic Arts Practice

Registered Supervisor and Professional Member ANZACATA

Carla van Laar is a painter and therapeutic arts practitioner from Australia. Born in Brisbane, Carla is first generation Australian on her Dutch grandparents side, and 7th generation through her maternal bloodline who were mostly English and came to Australia in the early colonisation of the 1800s. Carla currently lives and works in Victoria, residing between Wurrundjeri country in Melbourne, and Boon Wurrung country in Inverloch, paying deep respects to the First Peoples of the Kulin Nations whose land was never ceded and will always be Aboriginal land. Identifying as a cisgender woman, Carla is passionately disinterested in socially constructed identities that disempower anyone. Carla has over 25 years’ experience working with people and the arts for health and well-being in community organisations, justice, health and education contexts.

Carla’s first book “Bereaved Mother’s Heart” was published in 2007 and broke social taboos about maternal grief. From 2008-18 she established and ran an independent art therapy studio and gallery in Melbourne. Her Doctoral research “Seeing Her Stories” continues the mission to make women’s stories visible, through art.

Carla has lectured and supervised Art Therapy students at RMIT, MIECAT and currently the IKON Institute. She is a practicing artist and in 2018 received an Artist Fellowship at RMIT’s creative research lab, “Creative Agency”. She insists on being part of a creative revolution in which art re-embodies lived experience, brings us to our senses, makes us aware of the interconnectedness of all life and is an agent of social change.

Carla’s new book “Seeing her stories” presents her research into making unseen stories visible through art, and is available to read for free online here or purchase a hard copy of the full colour hard cover coffee table book here.

One Comment

Jade Lynch

What a wonderfully inspiring story…change most defiantly does come by facing taboo subjects… this changes minds/hearts thereby changing society. So very powerful!

Thank you for your contribution in forging change by addressing such topics

Kind Regards Jade Lynch